Only 4.5 years late, right? Well, not really, this is just another idea I came up with. It’s my firm belief (I’m sure it won’t be a shock, considering I’m running this site) that the best way to build your team is from within, and then supplement your homegrown core with talent from the outside in areas where you are weak. Many teams have done this (Cleveland, most recently) and the benefits are two fold. First, the cheapest talent is the kind you draft (or sign internationally) because you don’t have to give up anything (other than money) to acquire these players. Second, you have control of these players for 6+ years, which many times will take a player close to the peak of his production level. Now, before we go further, a quick qualifier. A strong farm system and a strong core of youth doesn’t always translate into wins. Cleveland, the example I gave above, has developed a really strong core of young players (Sizemore, Perralta, Lee, Martinez) but they struggled in 2006, though there is good reason to believe they were unlucky. However, the actual results of the team at the major league level is the last step of the process. As Phillies fans can see, with the likes of Cole Hamels, Ryan Howard, Brett Myers, Chase Utley, Jimmy Rollins and Pat Burrell, a strong young core sets your team up for years down the road, you just need a competent general manager to add the right complimentary pieces. Mark Shapiro might have failed there in Cleveland, or they might have just been unlucky.

So, that brings us to today’s essay. Players taken in the 2002 draft have now been in the Phillies system for 5 seasons (really 4.5, since players taken in June 2002 only had a half year, if they signed right away) so we can start to draw some conclusions about the draft and what might have been. I’m not looking for an avenue to bash our former GM Mr. Wade, because I really don’t know how much impact he had, many GM’s trust their scouting directors and their scouts, and just deal with issues like going above slot or avoiding a guy they perceive as a big injury risk. So, when reading my grades, consider them a grade of the entire Phillies drafting machine, not just one guy.

Here’s the way I’ll lay this out. I’ll break down the first 10 rounds of the draft, and then after that, just discuss the next ten picks together in shorter form, and do that until the final pick. I’m going to use a grading school similar to the 4.0 college grading system:

A = 4.0

A- = 3.5

B+ = 3.25

B = 3.00

B- = 2.75

C+ = 2.50

C = 2.00

C- = 1.75

D+ = 1.50

D = 1.25

D- = 1.00

For the first 10 rounds, I’ll give each pick a grade, then I’ll grade rounds 11-20, 21-30, 31-40, and 41-50 as a whole, with the letter grade above. Add then scores together, divide by 14, and we’ll have the final draft grade. Sounds like fun, huh? My criteria for determining the grade of each pick/round is pretty simple. 60% comes from the player’s performance. Did the guy perform well in the system? Was he a flop from the get go? Was he strong early and then struggled? 35% will come from the longevity of the player. Is he still in the system? Is he still in pro ball? Did he wash out after 1 year? If you’re drafting guys who play 1 season then quit baseball, you’re squandering resources. Maybe you can’t know that before hand, but that’s why you do your homework on these guys, and that’s why area scouts and crosscheckers get paid to watch high school kids play. The final 5% will come from the guys taken after the pick, and before the next Phillies pick, and basically any other wildcard criteria I choose to use. Did the Phillies pass up a kid who became a future star to draft someone who flopped? Again, maybe that was bad luck, but someone has to be accountable and this is my grading system, so they can deal with it! Ok, I got carried away there. Basically, this is just going to be a fun exercise for me, my grades really don’t mean anything, it’s just a fun way to look at the draft in more detail. The deeper the pick, the lower the expectations. In other words, if the Phillies get a major league contributor in the 25th round, they’ll be rewarded for it. Without further delay, let’s begin

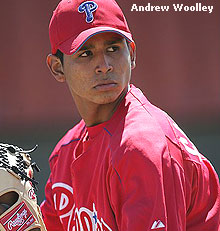

1.17: Cole Hamels, LHP. How’s this for a start to your draft? Hamels’ history is well known, but for those who are a bit foggy, here’s how it happened. Hamels broke his arm his junior year of high school, and because of it, his draft stock dropped. He was considered a top 5-10 pick before the injury, and was considered very advanced for his age with much more polish than most high schoolers, and an already established changeup. When he broke his arm, despite a good senior year, he dropped in the first round and the Phillies gambled. The pick was questioned almost immediately, but the Phillies stood firm. Hamels, when actually on the field, was brilliant at every level and showed people why the Phillies were so in love with him. Hamels’ minor league numbers were video game like, but he was bogged down every season by a number of medical maladies until finally staying healthy (for the most part) in 2006. He pitched 181.1 innings in 2006 across 4 levels after having thrown a total of 152 innings from 2003-2005. After a slow start at the big league level, he turned it up a few notches and finished the season strong, posting a tremendous 9.86 K/9 rate and a solid 1.25 WHIP. Looking back, this was a huge gamble, and though people doubted the pick even mid way through May 2006, it looks like Hamels has proven worthy. Grade: A- The only reason it’s not a straight A is because Hamels still does have some injury/durability concerns, but if 2007 is a repeat of 2006, healthwise, this becomes an A.

2.17: Zach Segovia, RHP. Segovia was dominant in high school, including an astouding 150 strikeouts in 77.2 innings pitched his senior year. He already had a large, strong body build, a plus fastball and a plus slider, so the Phillies felt he had a decent amount of polish for a high school player. He had a scholarship to Florida but signed with the Phillies and was sent to the GCL. He started well, he performed well at Lakewood in 2003, and then he hit a common (at least it’s becoming) roadblock, in needing Tommy John surgery. The surgery has become common that it now isn’t looked at as a probable career ender, and some pitchers even thrive moreso after surgery. Segovia missed all of 2004 and was assigned to Clearwater in 2005. He struggled, but many attribute this simply to trying to rebuild arm strength and shake off the rust. He re-established himself in 2006, and all the qualities the Phillies liked about him pre draft came back to the forefront. He still projects as a back of the rotation starter/7th inning reliever, and his odds of making the big leagues and contributing is pretty good right now. His grade gets dropped 1 level because the Phillies had the chance to draft Brian McCann, who could be a cornerstone piece of the core, but chose a pitcher in this slot. There weren’t too many other options between this pick and the third round pick, so only one grade drop. Grade: B This was a good pick at the time, because Segovia flat out dominated in high school and had all the makings of a top flight pitcher. His role is still a bit cloudy, so he doesn’t get a B+ just yet.

3.17: Kiel Fisher, 3B Houston, we have a problem! The Phillies, to their credit, forsaw the Scott Rolen exodus and decided to try and fill the void by drafting multiple third baseman in hopes of adding some dynamic talent at a position they knew was weak across the board within the system. Fisher was a solid high school bat, he had great raw tools, the Phillies loved his swing, etc etc. Well, Fisher struggled from the get-go, and was forced to repeat the GCL in 2003, which isn’t a good sign early in your career, but isn’t the end of the world. In his second trip through the GCL, he lit it up with a .908 OPS, and was promoted to Batavia, where he put up a solid .874 OPS in 96 AB’s to cap the 2003 season. Things were looking good…..then trouble hit. Fisher sustained a lower back injury that required surgery, and he subsequently missed the entire 2004 season. Lower back injuries for position players (and anyone really) are bad news. Fisher came back in 2005 and spent the entire year at Lakewood. Unfortunatey he hit just .173 with a .443 OPS in 98 AB, and that proved to be his last action in professional ball. Grade: C-. Honestly, I think I’m being generous here. The Phillies drafted Fisher here based on need rather than raw talent, and I can’t say I agree with that philosophy so early in a draft. Between this pick and their 4th round pick, pitchers Rich Hill and Josh Johnson were picked, and both have huge upside, with both already showing flashes of brilliance in 2006, not to mention Jeff Baker, who at the time, was still playing third base, though he has since moved to the outfield in Colorado.

4.17: Nick Bourgeois, LHP. One word sums up this pick for me. Blech. The Phillies, in prior years, had kind of neglected left handed pitchers, but seemed to have a knack for plucking good right handers (Myers, Madson come to mind), but in 2002 they tried to focus more on lefties. Bourgeois was drafted out of Tulane as a junior, but his numbers were fairly unimpressive, even in his junior year, where he posted a 3.29 ERA with an 8.92 K/9 and 3.52 BB/9. The strikeouts were nice, the walks not so much. The Phillies, upon drafting Bourgeois, said they didn’t think he had top of the rotation stuff, but could be a good #4 or #5 starter. He didn’t have a ton of velocity (87-88, topped out around 90), but had a good 12-6 curveball. To me, at this point, this just seemed like a bad pick. The Phillies were admitting he didn’t have impact potential, he was already tabbed for the back of the rotation (normally you start with higher goals and end up here) and to me, in the 4th round, you have to do better. After being drafted, he went to Batavia and was fairly unimpressive in only 18 innings. Nevertheless, he was sent to Lakewood in 2003. The strikeouts were still there (8.84/9) but unforunately, the walks were there too (4.99/9) and the end result, a 4.42 ERA, was not good for a college age pitcher at Low A. Again, the Phillies promoted him in 2004, this time to Clearwater. The results were similar, but actually got worse, with a lower K rate (7.25/9) and a higher walk rate (5.09), with an ERA of 4.94. The result? He was released and picked up by Seattle. He struggled in 2005 for Seattle, and hasn’t pitched in pro ball since. Grade: D- I think my reasons are clear here. Low ceiling pick, poor results, out of the org in just 2.5 seasons. Not good at all. While the bluechippers aren’t plentiful in round 4, the Phillies had the chance to grab Delwyn Young, a solid 2B in the Dodgers org, as well as Hayden Penn, one of the better pitching prospects in the Orioles system, who went early in the 5th round.

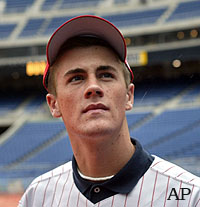

5.17: Jake Blalock, 3B. Ah, Jake Blalock. This pick was the follow up to Operation Third Baseman that I talked about earlier with the Fisher pick. Blalock played shortstop in high school, but was drafted as a 3B mainly because of his size, with some feeling he’d outgrown the position. His biggest strength was his baseball pedigree, being the younger brother of Hank Blalock, a quality hitting prospect for the Rangers at the time, and the son of a baseball coach, Sam Blalock. The Phillies liked his physical tools and felt he could play 3rd, 1st, or RF, possibly even catcher. He had a scholarship to Arizona State, but opted to sign and was sent to the GCL. At this point, it looked like a solid pick. At the time, I felt he was a good value in the 5th round. He had position versatility, he had a lot of potential, but like every high school guy, he was a long way away. His first two seasons followed the normal path, that is GCL to Batavia, and the results (.669 OPS and .767 OPS) were less than inspiring. However, because of his youth and tools package, hope still remained. However, in 2004, it became clear that Blalock’s future would be in the outfield, which reduced his value somewhat, as his bat would be his main contribution. His 2004 was good, not great, with a .799 OPS at Lakewood…average on base (.350) and decent slugging % (.449), but you were kind of expecting more, especially now that he was playing the outfield. 2005, things took a turn in the wrong direction as he put up a .747 OPS at Clearwater. The plate discipline was still there (.359), but the power was completely gone (.388 slugging), and that was a big problem. Light hitting outfielders only survive if they play lights out defense (normally center field, Jake was always corner bound) or they steal a ton of bases (he stole 28 bases total from 2003-2005) so he was in trouble. Blalock was traded along with Rob Tejeda to Texas for Dave Dellucci right before the beginning of the 2006 season, and may have sealed his fate with a .711 OPS at doube A Frisco. I haven’t read up on his future, but I’d guess 2007 will be his last shot, or 2006 might have been it. Grade: B- Maybe I’m being generous here. Blalock looked real good as a high school prospect. Good background, good tools, high baseball IQ. Unfortunately, he just didn’t make it work. Grade drops to B- because two quality arms, John Maine and Scott Olsen, were taken in the 6th round before the Phillies next pick, though admittedly, a position player was probably needed here.

This concludes Part 1. Let’s do a quick recap:

Hamels: A-

Segovia: B

Fisher: C-

Bourgeois: D-

Blalock: B-

GPA: 2.4. That’s around the B- range. Part 2 will come either later today or tomorrow. If you have quibbles with my grades, let me know, if you make a convincing argument, you just might help Eddie Wade make the honor roll.